There has been no better storyteller than the late Gary Paulsen, author of 200 books and best known for the adventure survival masterpiece Hatchet, the basis of a motion picture set in the Alaskan wilderness.

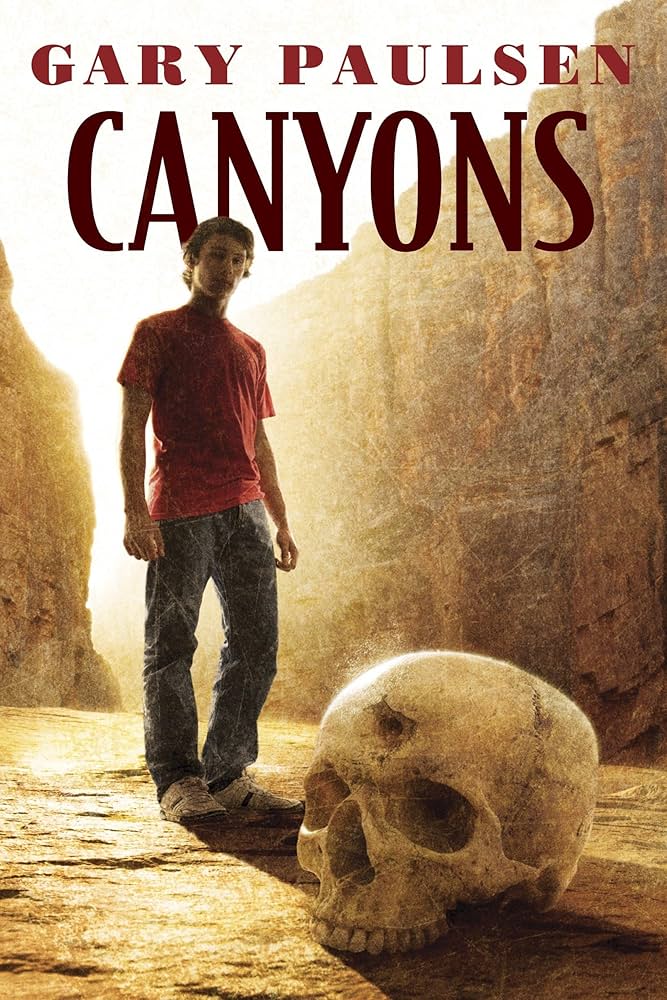

Canyons may be his best book, though. It is a story of two youths’ paths to manhood, separated by more than a hundred years, but bound by an extraordinary commitment to find closure.

Coyote Runs is a 14-year-old Apache warrior; Brennan Cole, 15, lives in New Mexico, near the canyons that Coyote Runs knows well. In 1864, during a horse raid across the Mexican border to prove his manhood, Coyote Runs is chased for days back to New Mexico, finally wounded in his leg by a rifle shot that kills his horse. He drags himself up a sandy slope and hides under a rock outcropping, depending on his spirit protector. But a bloody trail leads the Cavalry to the boy, who watches the end a rifle barrel find his forehead.

A century later, Brennan, his mom, her boyfriend, and eight pesky eight-year-old boys are camping in a New Mexico canyon. Seeking quiet and privacy, Brennan pulls his sleeping bag up a sandy slope and unfurls it under a rock outcropping. He crawls into his bag, so ready for rest.

”What’s that?” he thinks. He sits up, digs under the sand and finds a round rock—no, it is a skull. There is a hole in the skull just above the eyes and a much bigger void in the back.

Thus begins Brennan’s quest and he will not–no matter the roadblocks and consequences–quit until he discovers who died in that canyon and brings closure to the boy’s spirit, whose words guide him.

This week, I returned to Canyons, which I had read to my sons and to hundreds of students. It didn’t matter that I knew the spellbinding conclusion. Like all those times, my heart hung on Gary Paulsen’s every word.